I've been musing lately about a problem that has stubbornly resisted my attempts at solving it for quite some time; indeed, I sometimes wonder if I've made any headway at all in all the years I've spent reflecting on it. Perhaps I should pay heed to the title of my own blog - namely

tao - and plumb a bit of tao's timeless wisdom. To wit, maybe I ought to treat my problem not as a "thing" that needs solving, but as a transient stepping-stone on a timeless path toward gradual self-enlightenment.

"What is beauty?" I [S Nachmanovitch] asked him that night. He [Gregory Bateson] said, "Seeing the pattern which connects." (quoted from Old Men Ought to be Explorers, by S. Nachmanovitch)

My "problem" is to find the "optimal feature space" in which to describe the aesthetic sensibilities of particular artists; that is, essentially, to find an objective language (or, least as objective a language as possible) to describe the subjective propensities of, and differences between, individual painters, musicians, or photographers. We all "know" the difference between, say, Mozart's music and that of Beethoven; or the difference between a painting by Matisse and another by Picasso. Sometimes the differences, as in these "obvious" cases, are striking. In other cases, the differences may not be so clear cut: if one was, a priori, unfamilar with the works of

Minor White and

Brett Weston, for example, some of their respective abstracts may appear - superficially at least - as aesthetically indistinguishable.

Somehow, perhaps in the way that Malcolm Gladwell calls "thin slicing" in his book

Blink, we all make quick, largely unconscious, assessments about makes one work different from, or similar to, another. We can sometimes analyze - after the fact - why we made the decision of similarity or difference that we made. But (as Gladwell also points out in his book), we are not always able to articulate the precise feature-space decomposition we used to make our rapid-fire decision (because our subconscious thought-process does not always percolate up to the conscious level); nor can we really be sure that whatever feature-space decomposition we are able to articulate is an accurate reflection of what our unconscious information processing. Of course, often our thin-slicing attempts are also simply wrong.

The larger question, even if only as a thought experiment, remains. Let's start small, and not yet all-encompassing - a bit later I will generalize the question from photography to all forms of creative expression - and confine our analysis to photography alone, as an exemplar of a broader class of "art" and its associated larger class of aesthetic possibilities. We ask:

what is the optimal set of "features" (to be defined shortly) of "photographs" such that - in the N-dimensional abstract aesthetic space defined by these features as (roughly) orthogonal axes - two conditions are simultaneously satisfied: (1) the differences among photographs is maximized (with respect to sets of photographs produced by individual photographers), and (2) the differences between photographs produced by the same photographer (i.e., between any two images within a given photographer's own oeuvre) are minimized? In a sense, I want to perform a "simple" exercise of mathematical

pattern recognition, but without any (or little) initial sense of what space I'm performing it in, or even what I'm setting out to "recognize."

What do I mean by features? Well, any reasonably well-defined "parameter" that can be used to describe a photograph (which may, implicitly, involve both its physical attributes, as a print, and nonphysical attributes, such as subject matter or other contextual primitives). Of course, many different features exist (indeed, the set of possibilities is enormous); but not all features are as important in describing a work as others. More precisely, different sets of features will be better, or worse, at simultaneously identifying the works that are produced by a given photographer and distinguishing among bodies of works produced by different photographers.

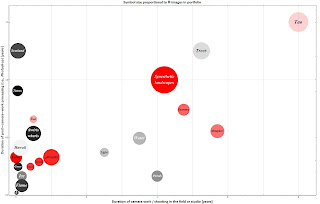

Thought Experiment #1. Schematically, we can imagine a 3-dimensional space (in general, the dimension D can be very large) consisting of the features f1, f2 and f3. As a thought experiment, imagine we have the collected works of three of photographers (A, B, and C; that we "code" using the colors red, blue, and green). We classify each photograph, of each photographer, according to where in the feature space in lives. It does not matter whether the "points" in this space are cleanly defined or not; the only thing that matters for this thought experiment is the fact that every work by each of the three photographers is classified according to the values of the three features we have used to define this particular "aesthetic space" F = {f1, f2, f3}. As a concrete example, the three features might be: f1=average hue, f2=degree of local constrast, and f3=number of triangular shapes. And, indeed, as we might expect of such a loose (random almost) set of parameters, we would not be surprised to learn (if we actually went to the trouble of performing this experiment) that these features do little to distinguish among our three photographers. Our plot of their respective oeuvres might look something like this...

But now, suppose we are a bit more clever than this. Suppose, after carefully studying the works of these three photographers, we discover a new set of features - {f1', f2', and f3'} - such that, in this new aesthetic space, F', the same body of work now appears considerably more tightly clustered:

Here we see - by direct visual inspection - an "obvious" distinction among the photographers A, B, and C. Moreover, we see that work produced by a

given artist is itself clustered around a relatively small volume of the full aesthetic space. "A" is obviously confined to one region, separate from (in this case) the volume of space occupied by "B," and both are distinct from the volume occupied by "C."

My point here is not that a feature space within which such a decomposition is possible exists - it may, or may not, for a given set of artists; but only that it suggests an interesting and deep question about what such a set of features - that simulataneously minimizes the differences among a given photographer's works and maximizes the distinction among the works of different photographers - might actually look like! I suspect it may not be like anything we would intuitively expect; if our intuition is anything like what we learn in the standard art and graphics design books. I doubt very much whether the "core features" would include such standard-issue measures as "contrast" and "tone" (though they may very well these). I wonder, too, at just how far separated the artist's "oeuvre clusters" can be made to be, while the spread of each artist's own cluster of works is simultaneously minimized.

One can play other thought games too, of course, For example, having defined some aesthetic space, and having plotted a given artist's current oeuvre - say, what the artist has produced during the last five years of work - we can trace how the artist evolves, using the first plot as a reference. Does the work remain more or less in the same "cloud" of points, so that the artist does not stray too far from his (possible innate?) aesthetic? Or does the cloud slowly dissipate, and reform in another region of the same aesthetic space? Or does the cloud diffuse outward to fill most, or all, of the "old" aesthetic space, thus suggesting that a new feature space - some F'' - exists, and in which the same artist's evolving oeuvre again assumes a cloud-like form?

Thought Experiment #2. Here is an even deeper question; and, truth be told, the real object of my rambling quest. Suppose we have managed to find a special "core aesthetic" space that does precisely what our thought experiment imagines. That is, imagine we have an aesthetic space defined by a special set features (whose relevance, for the moment, is confined solely to photography) that both maximizes the difference between different photographers, and - simultaneously - minimizes the differences between individual photographs of a given photographer. Suppose, further, that we carve out of that space a special set of photographs (and, by association, a special set of photographers) which maximize - for lack of an objectively better-defined word - photographic

beauty. Now, imagine we do exactly the same thing (i.e., play the thought experiment as described above) for

all of the different kinds of creative endeavors that exist: music, sculpture, literature, mathematics, physics, ... The analog of (generic) "beauty" in art or photography might be - in the case of mathematics, for example - "truth" (as in the truth of theorems); in physics, "beauty" may be aligned with "physical laws" (the "truths" of nature), and so on. What is the underlying

meta-pattern that connects the patterns?

Here is my question (and I'll stop at this point):

might there be a "universal aesthetic meta-map" that transforms the set of features of one aesthetic space (that describes art, say) to another set of features that describe a different aesthetic space (mathematics, say) but which leaves the measure of "beauty" that is appropriate for each kind of space invariant?

"We do not want merely to see beauty...we want something else which can hardly be put into words; to be united with the beauty we see, to pass into it, to receive it into ourselves, to bathe in it, to become part of it." - C. S. Lewis

"Beautiful" art or music, "physical laws" in physics, and "theorems" in math may be - in a truly fundamental sense - indistinguishable, but only if the analog of "beauty" is correctly defined , and interpreted, in each respective space. Indeed, I suspect that if only we were clever enough creatures to be able to simultaneously apprehend and reflect upon vast multidimensional features spaces, it would only be a matter of "shifting our perceptual / aesthetic axes" (so to speak) for us to be able to transform our endeavors from one creative space into another. Imagine being able to "prove a mathematical theorem" by working on the problem as though it were an art project (and the object of which - in the art space - is to produce a "beautiful work of art"). But whatever space we happen to find ourselves in at a given moment, the object of our quest (and the ultimate arbiter of our creative progress) remains indefagitably the same:

truth.

Postscript #1. The way I presented my thought experiment, a (God like)

external agent is needed to view the universe of artists and their work to construct (and plot the creative progress in) a D-dimensional aesthetic space. In fact, one can argue that each artist (indeed, each living being) is doing precisely that, ceaselessly, tirelessly, throughout its existence. We are all seeking to be as distinct as possible from all other living beings, even as - at the same time - we desire to be be as integrated into our local cultural / creative fabric as well. It is this insoluble yin-yang tension that drives all self-motivated dynamics; and perhaps all creativity. This fundamental idea of the universe consisting of simultaneous and seemingly antithetical tendencies of

integration and

distinction (or

assertiveness), at all levels of a multidimensional hierarchy, was introduced by author / philosopher

Arthur Koestler in a book called

Janus. He called all such creatures that strive to do this

holons.

Postscript #2. The idea that there is a core universality that underlies all forms of art - all

life - is certainly not born in this humble blog entry. In fact, much of my thinking on the subject derives from, and has been shaped by, a magnificent four volume work called

Nature of Order by architect / visionary Christopher Alexander (about whom I've written

before on my blog).

Postscript #3. A similar idea to the one presented above as thought experiment #1 (but in the context of cosmology) - and developed more completely on a semi-rigorous mathematical level - was proposed a few years ago by physicists Julian Barbour and Lee Smolin. They called it

extremal variety. Barbour has published another article on this subject in the

Harvard Review of Philosophy.