"You don't take a photograph, you make it." - Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams introduced the idea of

previsualization into the photographer's lexicon (see my

earlier Blog entry on Adams); a term he used to label the importance of imagining, in your mind's eye, what you - as a "photographer" (not just a snapshooter) - want the

final print to reveal about a subject (and to communicate of your artistic vision). Without this preconception, wherein much of the artist's creativity resides (specifically, in the implicit steps that must be followed, starting with composition, focal length, shutter speed, filtration, and so on, in order to achieve the previsualized image), the resulting "photograph" is at best a product of inspired "luck" (or intuition) and, at worst, shallow and unable to communicate meaning.

A common "lament" of many of today's amateur photographers - particularly those who fancy themselves as following in the footsteps of pioneers such as Adams - is that their point & shoot camera (or, worse, their super-duper-sophisticated, modern digital single-lens reflex, or DSLR) simply doesn't produce the kind of pictures they want; or, though it is rarely stated this way, doesn't produce what they see in their mind's eye!

The reality, of course, is that no camera, however sophisticated, can "guess" what is in the artist's mind, and then, having correctly guessed, perform whatever digital prestidigitations are required to produce the "perfect" digital file; a file that, moreover, must then also be printed correctly on some chosen combination of printer and paper. It is ironic that as the power of our tools (including cameras, software and printers) increases, and becomes more affordable and user-friendly, the desire to use our tools (to convert a simple point & shoot image into a photograph that more closely resembles an inner vision) generally declines. We expect more out of our cameras; and when the camera (through no fault of its own or its manufacturer) inevitably fails to deliver what we demand, we just as inevitably blame the technology.

The simple lesson of previsualization - that is as applicable today as when Ansel Adams was capturing his spectacular images of Yosemite National Park - is that while one might get lucky, and capture a fine image, the far more likely result of approaching a subject without an idea already in mind is disappointment.

Fine art does not just

happen; it requires a (sometimes prodigiously willful) act of

inspired, participatory creation. The artist must be a willing and active participant in

all of the steps leading up to the image's final (typically

print) form; including the act of capture (see my entry on Galen Rowell's

participatory photography) and the (often elaborate) digital equivalents of analog darkroom tonal manipulations.

Case in point: consider the two images at the top and immediately below. Arguably, neither the before (straight out of camera) image shown above, nor the after (digitial darkroom manipulation) image that appears at the end of this paragraph belong to the lofty heights of fine-art photography as practiced by Ansel Adams. Indeed, depending on one's aesthetic tastes, neither image may even be terribly "interesting" to look at;-) However, despite the fact that the two images are visual imprints of the same thing (a broken window), no one will argue that they are very different!

I can confidently assert that the after image is precisely what was in my mind's eye when I pressed the shutter. More to the point, the objectively rather bland before image of the broken window was very faithfully rendered by my DSLR. But it is emphatically not what I wanted the print to look like, and which I knew I could create by having previsualized the process necessary to get there at the instant I pressed the shutter. The bland before image simply needed a "bit of work" to get it from its "faithful" form, into a state in which I, as photographer, am satisfied that it (at least) stands a chance of communicating a bit of my aesthetic vision.

If you, like me, are moved by the mysterious power of the after image, in which a subtle, ethereal "glow" seems to radiate from the black void (the "existence" and communication of which required the digital equivalent of selective dodging and burning, and an attention to the distribution of tones in the RAW image), you must agree that it would have been a great shame for me to have glanced at my DSLR's output, see the "uninteresting" recorded image, and, with perhaps a sad sigh for emphasis, conclude, "Well, better next time," before deleting the file from my compact flash card!

A nice way to summarize these musings, and as an homage to another of Adams' favorite sayings, is to think of the DSLR's RAW output as an "equivalent" of a musical score (the image "exists" but in an essentially latent, as-yet-unrealized form); what the photographer subsequently does with that RAW file in the digital darkroom is analogous to a performance! (The "performance" can - indeed, undoubtly will - change in time as the photographer's own skills, tastes and "eye" evolve. If there is a single deep lesson that photography teaches us, it is that there is no such thing as the one "true" objective reality ;-)

A few older examples of

Before and

After images can be viewed on

this page.

One of the most magical properties of photography is its ability to transform the ordinary - by which I mean common, everyday things and places - into something else: sometimes this "something else" is the same ordinary object(s) but with a subtle uncommon twist; sometimes it is the same "ordinary" object(s) but observed from an unusual perspective with less-than-common lighting; and sometimes (in those improbably rare but magical moments!) the photograph captures something that at first sight appears to be the same as something you recognize as utterly ordinary and uninteresting, but which upon further reflection shines radiantly with an ethereal glow, as though a portal into a hidden dimension of beauty has been revealed, if only for an instant. The "image" - in such rare instances - points to something that is simultaneously obviously of this world, and just as obviously not!

Sadly, I have no examples of the latter category to show you, though each time I go out with my camera, a part of my soul waits (yearns, hopes, dreams...) expectantly, for the world to bestow this joyous gift; I know it exists, for I have seen it - many times! - if only in my mind's eye as I slowly bring my finger to the shutter, so as not to disturb the magic, and whisper a short prayer as I press it that the camera has captured what I see. Alas, it has not yet done so; but the beauty is too great to ignore and not share with others.

In the meantime, however, I do have a few humble samples from the first two categories...

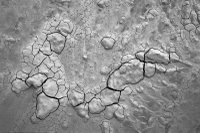

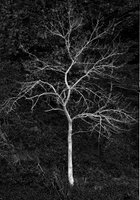

The "ordinary" objects depicted here are commonly known as mud, rock, tree, old glasses, a reflection in a puddle, and a fence on the beach.

One of the most magical properties of photography is its ability to transform the ordinary - by which I mean common, everyday things and places - into something else: sometimes this "something else" is the same ordinary object(s) but with a subtle uncommon twist; sometimes it is the same "ordinary" object(s) but observed from an unusual perspective with less-than-common lighting; and sometimes (in those improbably rare but magical moments!) the photograph captures something that at first sight appears to be the same as something you recognize as utterly ordinary and uninteresting, but which upon further reflection shines radiantly with an ethereal glow, as though a portal into a hidden dimension of beauty has been revealed, if only for an instant. The "image" - in such rare instances - points to something that is simultaneously obviously of this world, and just as obviously not!

Sadly, I have no examples of the latter category to show you, though each time I go out with my camera, a part of my soul waits (yearns, hopes, dreams...) expectantly, for the world to bestow this joyous gift; I know it exists, for I have seen it - many times! - if only in my mind's eye as I slowly bring my finger to the shutter, so as not to disturb the magic, and whisper a short prayer as I press it that the camera has captured what I see. Alas, it has not yet done so; but the beauty is too great to ignore and not share with others.

In the meantime, however, I do have a few humble samples from the first two categories...

The "ordinary" objects depicted here are commonly known as mud, rock, tree, old glasses, a reflection in a puddle, and a fence on the beach.

Oh, and the image at the top of this entry, is a view from an "ordinary" hiking trail at a local park (Great Falls, VA side).

How uncommonly beautifully "common"! ;-)

Oh, and the image at the top of this entry, is a view from an "ordinary" hiking trail at a local park (Great Falls, VA side).

How uncommonly beautifully "common"! ;-)