I am both blessed and cursed with a need to simultaneously nourish two complementary sides of my soul:

physics and

art. So, typically, even as my camera and I happily enter an otherwise ego-less state of tranquil communion with nature's sublime forms and patterns, the "other" half of my soul inevitably intrudes - albeit gently - with somewhat more cognitively-inspired thoughts and impressions (and an occassional impromtu equation or two;-)

Thus we come to the subject of this Blog entry, which has to do with what may be a curious conceptual overlap between

ergodicity and

art (fused, I will argue, by a conscious act of

selection). "Ergodicity" is a technical term used in stochastic physics, that, roughly speaking, refers to any process whose "time average" (taken over a single realization) converges to the corresponding "ensemble average" (taken over many realizations). At the risk of oversimplification, think of an ergodic process as one in which one may understand what happens at a

single point (in a system's phase space) by either averaging over what happens at that one point over a long time, or by averaging over what all of the points are doing at a given instant in time. In other words, for an ergodic process, a

spatial average at one time is equivalent to a temporal average at one spatial point.

What does this have to do with art, photography, and abstraction? Well, one way to characterize the difference between what a traditional artist (such as my

dad) does and what a fine-art photographer (such as what I am slowly trying to teach myself to become) does - assuming each is exploring, in his/her own way, the conceptual equivalent of an

ergodic artistic landscape - is to look at how the two respective types of artists arrive at their art; or, more precisely, to look at how artists and photographers go about creating the

physical form of their art (a

painting or a

photograph).

The traditional artist sits at his easel (either in a studio or "in the field"), which thus defines a physical space-time "region" for his brush, and

actively creates the art on a canvas. To fully "understand" this traditional artist's

art - of which each individual painting is but one example - one can imagine taking a time-average over all possible art-works that the artist's brush can "create" over the artist's lifetime; or, equivalently, one can sample over all possible "mind states" that the artist traverses over his

internal artistic landscape (while sitting at the same easel at the same physical location!).

In contrast, the photographer wanders over (sometimes enormous stretches of) the physical landscape in hopes of

finding an exemplar or two of what it is he/she wishes to express though his/her photographs. The photographer's equivalent of the traditional artist's "brush" (which sits roughly at the same "point" in space and whose subtle movements reflect the artist's inner world) is the camera, which roams over the physical landscape in search of what is, effectively, an already completed canvas. While one can argue that the photographer also has a "brush" of sorts in the guise of a "darkroom" (analog or digital), the most important element of the photographer's "art" is also arguably the moment of "capture." In order to fully understand the

photographer's art - of which each individual photograph is but one example - one could imagine taking an average over all possible photographs that the photographer will choose to "create" over his/her lifetime; i.e., an average over all possible "physical states" that the photographer traverses in his search for exemplars of his inner artistic landscape.

Note that while both kinds of artists

select their work (out of all possible realizations in a huge multidimensional "art" landcsape), they do so in complementary ways. The traditional artist selects by sampling over an inner landscape of the mind/soul, commiting only those images to his/her canvas that communicate a desired vision; he "selects" to use one type of brush instead of another, and this color and quantity of paint instead of another, and so on. The photographer's selection is also born of an inner vision (as is true for

any art), but the selection is not made incrementally, as though the photographer has individual control over which pixels (on a digital camera's CMOS or CCD ship) will receive which signal; rather, the selection is made

all at once, when all the tones and textures and forms of a scene are just right for the finger to press the shutter. The photographer selects his art by literally

finding it, or, more precisely, by finding some worthy exemplar of the message the artist wishes to impart via his art.

Toward the end of his life, my dad (who passed away in 2002) created some truly extraordinary art that might conventionally be "labeled" as abstract expressionist. A generous sampling of his later work can be viewed

here.

While my own art also leans heavily to the abstract, I have not been blessed with my dad's gift of expression with brush and paint. I must instead rely on my inner eye to guide me (and my camera) to examples of "abstract art" as they appear in the world. Out of all such exemplars that I thus discover, I "select" those that come as close as possible to what I

would have created myself, if only I had my dad's ability. Such is the photographer's art.

While my dad looks inward to

create such works as...

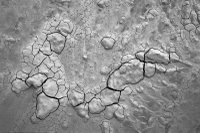

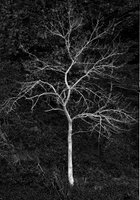

...I must instead hope to

stumble across some composition, somewhere

out there in the real world (whether by chance alone or enlightened synchronicity!), that captures - in an abstract form -

what is in my mind's eye (that I cannot express nearly as well with my camera as my dad did with his brush). I must thus content myself with images such as these...

While I have not "created" any of these images, in the strictest sense of the word, I do take responsibility for carefully - and, I hope, artfully -

selecting precisely those ineffable points in time and space that, when rendered by my eye and camera, communicate essentially the same message I would have communicated had I had my dad's artistic genius (and substituted a brush, paint and canvas for my camera, lens and compact flash card.)

Ultimately, the purest form of art, whether it is manifest in painting, photography, sculpture, architecture, or dance - or

all of these things, at different times of an artist's life - resides in the life and soul of the artist. Art is seldom found "in" (or confined to) the work that an artist produces, but can readily be observed - even by non-artists - by looking closely at how the artist creates his work (and lives his life!):

art is a soul's meta-pattern of willful creation.

I know this to be true, because I saw first-hand how "art" is lived (by a soul known to others as Slava the artist, and whom I simply called "dad"). To help heal my heart after my dad's passing, I sometimes imagine that, somewhere on my multidimensional ergodic artistic landscape, my photography and his art have finally brought the two of us together to some magical space-time-averaged "point" where we are each able to see the beauty of the world through the other's "artistic" eye.

Finally, how does all of this connect back to "ergodicity" as defined at the start of this entry? My "theory" is that just as one can get "to know" a traditional artist (his "style") by looking over a lifetime's worth of work (i.e. by taking a time average over all the works the artist can produce while sitting in roughly the same point in physical space), so one can get "to know" a photographer by looking over all possible images the photographer can take from all possible vantage points in space (i.e., by taking a spatial average over all possible images the artist can take at one time). Of course, this leads open the possibility (even likelihood) that the "styles" of artists change, and evolve, in time. But as a crude conceptual characterization of the fundamental difference between how traditional artists and photographers "create" their work I think it offers an amusing stepping stone.

At the very least, such musings (what might be called

ramblings by some;-) beg questions such as

"What does an "artistic landscape" look like?",

"To what extent does it characterize an artist's unique style and vision?", and

"How do different artists traverse this landscape in search of their art?"