I am about half-way through a superbly illuminating biography of Ludwig van Beethoven by Edmund Morris. Though short for a biography, Morris' writing style is so wonderfully succinct and poetic that reading this work is the linguistic equivalent of fine (though perhaps not quite Beethoven-esque) music. Highly recommended.

I am about half-way through a superbly illuminating biography of Ludwig van Beethoven by Edmund Morris. Though short for a biography, Morris' writing style is so wonderfully succinct and poetic that reading this work is the linguistic equivalent of fine (though perhaps not quite Beethoven-esque) music. Highly recommended.But the point of this blog entry is not Morris' Beethoven bio per se, but rather a brief muse on an interesting observation he makes on pages 72-73. By this time in the book, we are in March of 1798 (Beethoven's life spanned the years between 1770 and 1827), and Beethoven is already a young up-and-coming composer / musician. Importantly, his life intersected with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (albeit extremely briefly, in 1787, and but for one reported meeting) and Joseph Haydn (1732 - 1809). After hearing the 17 year old Beethoven play, Mozart was reported by a latter 19th century biographer (Otto Jahn) to have said, "Keep your eyes on him; some day he will give the world something to talk about" (though the veracity of this account is questioned by Morris). Beethoven, for his part, was said to have later commented on Mozart's own piano playing style as "choppy." But all of this is still an aside, as we move on to the grand'ole "papa of music" at the time, Haydn and one of Haydn's own performances in 1798 (which may, or may not, have been attended by Beethoven).

After a short self-imposed "retirement," Haydn reappeared on the public stage with a performance of a new composition (one destined to be his last work, and truly an inspired masterpiece by all acclaim) called The Creation. Morris notes that in this remarkable work, Haydn apparently presages several tonal and musical structures that the modern world would one day associate with Beethoven. Morris hypothesizes (and quickly dismisses) the idea that Haydn had consciously imitated some passages in a cantata Beethoven had shown him about eight years earlier, but speculates that perhaps the unconscious seeds of inspiration were nonetheless planted by Haydn's association with Beethoven. Since there are only twelve basic tones in the Western musical scale, it is inevitable that coincidental and otherwise similar use of harmonies and repetition will exist. But outright plagiarism is rare, on a conscious level (except in cases where it is blatantly obvious, and is a sad event when it happens of course).

So that started me thinking about the appearance of similar "unconscious seeds of inspiration" in photography. While the "tonal range" (here I am thinking more of subject matter and general expression rather than traditional black and white tones) in photography is obviously much larger than the dozen tones in music - after all, the number of things that photographers can take pictures of are essentially endless - nonetheless, the number of aesthetically meaningful core subjects (or more precisely, core subject classes) is much smaller.

How many "things" (or classes of things) can we really take pictures of? There is the general landscape, portrait, still-life, and photojournalism (among others). Each class, of course, contains many sub-classes. There are landscapes of deserts, of seascapes, of forests, and so on. Portraits may be of individuals, couples, artists, children, weddings, etc. At some point, however, either a true "novelty" is found - and remains just that, a novelty, either because it was done so well (or badly) that others are loathe to repeat it, or the subject matter was perhaps not as interesting, and/or of as lasting a value as first believed) - or a sufficiently unique perspective on an old subject is taken and the novel work thus serves to refine aesthetic meaning and boundaries. But similarity of approach and subject matter, if not downright repetition, is - in the long term - unavoidable. Just how many pictures of a mountain (or rocks, or lakes, or butterflies, or broken glass, ...) can one take? And at what point will one picture of a canyon look any other picture of a canyon?

Brooks Jensen, editor of Lenswork, published excerpts of a roundtable discussion with photographers on this subject about a year ago (in issue #76, May / June 2008), entitled "Fellow Travelers." The discussion was inspired by Jensen receiving a portfolio of grain elevators (which was subsequently published in issue #76) just as issue #75 was going to press with a portfolio of grain elevators by another photographer. Since the "new" portfolio had just as much aesthetic merit as the portfolio being published, the basic practical question was: "What is a publisher to do?" The deeper philosophical question, taken up by the photographers in the roundtable discussion, was / is: "Is there such a thing as parallel creative vision?" And, when does inspiration cross the line to become plagiarism?

A well known example of a "parallel creative vision" involves no less a figure than Ansel Adams. In 1942, Adams took his celebrated shot of Canyon de Chelly (in Arizona). Only later did he learn that it was essentially the same photograph - both in terms of composition and lighting - that 19th century photographer Timothy O'Sullivan took in 1873. We know that Adams knew - at some level - of O'Sulivan's image, because, in 1937, he lent an O'Sullivan album to Beaumont Newhall for the landmark exhibition on the centenary of photography. Adams' "reproduction" of O'Sullivan's photograph of Canyon de Chelly was entirely unconscious, and resulted from being in the same environment and executing the photographic process according to a similar aesthetic.

There are many examples of this ilk, of course; and "parallel creative vision" is certainly not confined to music or photography. In my own case, I recently discovered a similarity of vision with - and, in hindsight, not unexpectedly, a major artistic influence on me - British photographer Fay Godwin. It was Godwin's book Land, published in 1985, that was instrumental in my becoming as avid a photographer as I've become.

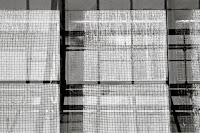

While in the process of selecting a set of images to exhibit at a local photography coop for our current hanging, I ran across one of my personal favorites from last year, which I call "Luminous Boundary" and you can see in small size at the top of this blog entry. Well, after the hanging, and while I was reareanging my shelves of books and journals in my study, I ran across Lenswork issue #48 (Aug / Sep 2003). Lo and behold, there is a photograph by Fay Godwin that is a virtual doppelganger of mine (or is my photograph a doppelganger of hers?) You can see Godwin's image on page two of the preview. While I can honestly say that I was not consciously aware of Godwin's image (which I had known about previously, and was reminded of that fact when I saw it again in Lenswork only after taking, processing, printing, and hanging my own shot), I cannot help feeling that I was also unconsciously motivated to "see" this particular shot when the opportunity presented itself.

The question I am asking myself is, "Would I have taken this shot, in this way, had I never known about Fay Godwin?" (Then again, in that case, the question itself may be moot since it is entirely possible I would never have decided to pursue photography!)

Postscript: While I was trying to find a direct link to Fay Godwin's image I was discussing above (I could not find it, but it is available on page 2 of the pdf preview of Lenswork #48), I ran across another "parallel vision" image, but this time it seems I have anticipated Godwin's discovery. The image is of Devastion Trail on the Big Island, Hawaii. Here is my image, taken (in color!) in 1983: I used slide film back then and this is a digitized image I made about ten years ago). And here is an image that Godwin took in 1988. Of course, in this case, I am certain that Fay Godwin had not one inkling that some unknown photographer named Andy Ilachinski was taking pictures in the same spot in Hawaii ;-)

Featured Comment (by Cedric Canard): "Good post and interesting question. Interesting in the possibilities it brings up. As you know Andy, I wrote a post which turned out to be very similar to one of yours and while I've only become a regular reader of your blog since, I have a vague recollection of coming across your blog some time in the past even though I do not recall reading the post that I covered prior to my writing it. Anyway upon reading this latest post of yours, some thoughts or memories came up and I'd like to explore these, with your permission.

I was reminded about the so called 100th Monkey experiment I read about many years ago. Where monkeys on one island learnt to do something and then monkeys on another island seemed to be able to do the same thing without the time lapse that it took the other monkeys to learn the same thing. As you know I too question the nature of thoughts. While thoughts appear to be mine I do have reservations. I can only speak for myself but many (if not most) of the thoughts that come into my head are uninvited and I do not know where they come from but I do know I cannot, in all fairness, call them mine. And though I will accept responsibility for any actions that stem from such thoughts including what I am writing now, I have to say that I have problems with claiming ownership to these writings or, for example, of the images I create. Perhaps what we call "my mind" is in actuality just a mind which is shared by all of us. So where a thought occurs to one it could just as easily occur to another especially when faced with the same circumstances. The fact that it happens in different times is most propably irrelevant when it comes to mind stuff.

In all likelyhood, you have probably taken more than one photo which has strong similarities to another photographers work but you may simply never know it. But I guess your question is asking whether a photograph (or mucical score) that we create has to be "seen/heard" first in order to be similar to another's creation. In other words if we create something unoriginal without the conscious intent of copying, is it a pre-requisite for us to have at some point, viewed/heard the original?

Advertising kind of counts on this premise. Adverts on billboards, television, magazines etc do not really brainwash us into wanting something we didn't even know we wanted or needed. Adverts simply aim to be captured by our subconscious so that when the time comes to make a choice between products the advertised product will come to the forefront of our memories and we will "choose" that product. Relating this back to photography, we may well "store" images we see in our subconscious which emerge when the opportunity presents itself and we are fooled into believing that we have done something original.

We'll never know if your "Luminous Boundary" would have existed without Fay Godwin's influence and I suspect it makes little difference. For me though, your story and your image have poked another hole in my belief that we are separate, in my belief of "me". And I sense that's a good thing because with that hole, seeing seems a little clearer."

How many "things" (or classes of things) can we really take pictures of? There is the general landscape, portrait, still-life, and photojournalism (among others). Each class, of course, contains many sub-classes. There are landscapes of deserts, of seascapes, of forests, and so on. Portraits may be of individuals, couples, artists, children, weddings, etc. At some point, however, either a true "novelty" is found - and remains just that, a novelty, either because it was done so well (or badly) that others are loathe to repeat it, or the subject matter was perhaps not as interesting, and/or of as lasting a value as first believed) - or a sufficiently unique perspective on an old subject is taken and the novel work thus serves to refine aesthetic meaning and boundaries. But similarity of approach and subject matter, if not downright repetition, is - in the long term - unavoidable. Just how many pictures of a mountain (or rocks, or lakes, or butterflies, or broken glass, ...) can one take? And at what point will one picture of a canyon look any other picture of a canyon?

Brooks Jensen, editor of Lenswork, published excerpts of a roundtable discussion with photographers on this subject about a year ago (in issue #76, May / June 2008), entitled "Fellow Travelers." The discussion was inspired by Jensen receiving a portfolio of grain elevators (which was subsequently published in issue #76) just as issue #75 was going to press with a portfolio of grain elevators by another photographer. Since the "new" portfolio had just as much aesthetic merit as the portfolio being published, the basic practical question was: "What is a publisher to do?" The deeper philosophical question, taken up by the photographers in the roundtable discussion, was / is: "Is there such a thing as parallel creative vision?" And, when does inspiration cross the line to become plagiarism?

A well known example of a "parallel creative vision" involves no less a figure than Ansel Adams. In 1942, Adams took his celebrated shot of Canyon de Chelly (in Arizona). Only later did he learn that it was essentially the same photograph - both in terms of composition and lighting - that 19th century photographer Timothy O'Sullivan took in 1873. We know that Adams knew - at some level - of O'Sulivan's image, because, in 1937, he lent an O'Sullivan album to Beaumont Newhall for the landmark exhibition on the centenary of photography. Adams' "reproduction" of O'Sullivan's photograph of Canyon de Chelly was entirely unconscious, and resulted from being in the same environment and executing the photographic process according to a similar aesthetic.

There are many examples of this ilk, of course; and "parallel creative vision" is certainly not confined to music or photography. In my own case, I recently discovered a similarity of vision with - and, in hindsight, not unexpectedly, a major artistic influence on me - British photographer Fay Godwin. It was Godwin's book Land, published in 1985, that was instrumental in my becoming as avid a photographer as I've become.

While in the process of selecting a set of images to exhibit at a local photography coop for our current hanging, I ran across one of my personal favorites from last year, which I call "Luminous Boundary" and you can see in small size at the top of this blog entry. Well, after the hanging, and while I was reareanging my shelves of books and journals in my study, I ran across Lenswork issue #48 (Aug / Sep 2003). Lo and behold, there is a photograph by Fay Godwin that is a virtual doppelganger of mine (or is my photograph a doppelganger of hers?) You can see Godwin's image on page two of the preview. While I can honestly say that I was not consciously aware of Godwin's image (which I had known about previously, and was reminded of that fact when I saw it again in Lenswork only after taking, processing, printing, and hanging my own shot), I cannot help feeling that I was also unconsciously motivated to "see" this particular shot when the opportunity presented itself.

The question I am asking myself is, "Would I have taken this shot, in this way, had I never known about Fay Godwin?" (Then again, in that case, the question itself may be moot since it is entirely possible I would never have decided to pursue photography!)

Postscript: While I was trying to find a direct link to Fay Godwin's image I was discussing above (I could not find it, but it is available on page 2 of the pdf preview of Lenswork #48), I ran across another "parallel vision" image, but this time it seems I have anticipated Godwin's discovery. The image is of Devastion Trail on the Big Island, Hawaii. Here is my image, taken (in color!) in 1983: I used slide film back then and this is a digitized image I made about ten years ago). And here is an image that Godwin took in 1988. Of course, in this case, I am certain that Fay Godwin had not one inkling that some unknown photographer named Andy Ilachinski was taking pictures in the same spot in Hawaii ;-)

Featured Comment (by Cedric Canard): "Good post and interesting question. Interesting in the possibilities it brings up. As you know Andy, I wrote a post which turned out to be very similar to one of yours and while I've only become a regular reader of your blog since, I have a vague recollection of coming across your blog some time in the past even though I do not recall reading the post that I covered prior to my writing it. Anyway upon reading this latest post of yours, some thoughts or memories came up and I'd like to explore these, with your permission.

I was reminded about the so called 100th Monkey experiment I read about many years ago. Where monkeys on one island learnt to do something and then monkeys on another island seemed to be able to do the same thing without the time lapse that it took the other monkeys to learn the same thing. As you know I too question the nature of thoughts. While thoughts appear to be mine I do have reservations. I can only speak for myself but many (if not most) of the thoughts that come into my head are uninvited and I do not know where they come from but I do know I cannot, in all fairness, call them mine. And though I will accept responsibility for any actions that stem from such thoughts including what I am writing now, I have to say that I have problems with claiming ownership to these writings or, for example, of the images I create. Perhaps what we call "my mind" is in actuality just a mind which is shared by all of us. So where a thought occurs to one it could just as easily occur to another especially when faced with the same circumstances. The fact that it happens in different times is most propably irrelevant when it comes to mind stuff.

In all likelyhood, you have probably taken more than one photo which has strong similarities to another photographers work but you may simply never know it. But I guess your question is asking whether a photograph (or mucical score) that we create has to be "seen/heard" first in order to be similar to another's creation. In other words if we create something unoriginal without the conscious intent of copying, is it a pre-requisite for us to have at some point, viewed/heard the original?

Advertising kind of counts on this premise. Adverts on billboards, television, magazines etc do not really brainwash us into wanting something we didn't even know we wanted or needed. Adverts simply aim to be captured by our subconscious so that when the time comes to make a choice between products the advertised product will come to the forefront of our memories and we will "choose" that product. Relating this back to photography, we may well "store" images we see in our subconscious which emerge when the opportunity presents itself and we are fooled into believing that we have done something original.

We'll never know if your "Luminous Boundary" would have existed without Fay Godwin's influence and I suspect it makes little difference. For me though, your story and your image have poked another hole in my belief that we are separate, in my belief of "me". And I sense that's a good thing because with that hole, seeing seems a little clearer."